We weren’t quite sure what would happen when we unleashed the power of children’s imaginations on the 21st century objects in the Modern British Childhood exhibition. But we were amazed at the results.

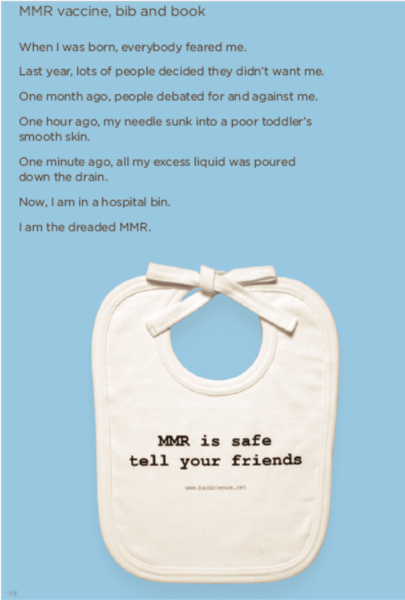

A ten year old girl gives the MMR vaccine a voice – “When I was born, everybody feared me”, a Lily Allen dress insists it’s “no gangsta” and a nine year old boy imagines his trainers squabbling in a cupboard, each pair fighting to be chosen first.

A 10 year old girl from Hackney writes about the MMR vaccine

While adult writers from 26 responded to 20th century objects in the exhibition at the Museum of Childhood, children from Rushmore Primary School in Hackney wrote about the 21st century objects on display.

Like the adults, the young writers had to respond in just 62 words – a sestude. The children wrote their sestudes during a series of workshops run by The Ministry of Stories, the creative writing and mentoring centre in East London.

Here, we ask the people involved what happened behind the scenes.

Getting to know the objects

Helen Roberts, Creative Learning Workshop Leader at the Ministry of Stories, is an Education Practitioner who specialises in community, museum and gallery projects. She devised and led four workshops for the children which took place over four weeks during the spring in 2012.

“Experiencing the Museum of Childhood’s collection first-hand was a huge inspiration for this project,” says Helen. “The children were clearly excited to have been invited to contribute to the Modern British Childhood exhibition, and took great pride in their writing. They questioned and critiqued the objects according to their own experiences, whilst responding to and reinventing them in imaginative and unexpected ways.”

Exploring poetry, rhythm and six word stories

Sarah Farley, a member of 26 who volunteers with the Ministry of Stories, describes the different stages of the workshops, where she acted as a writing mentor.

“During the first workshop at the museum we worked on describing objects in different ways, including writing about how a particular object made them feel. Rhian Harris, the director of the museum and curator of the exhibition, then introduced the actual objects and asked the kids if they’d like to write about them for the exhibition. The answer was a resounding Yes!”

The second and third workshops took place at the children’s school, and investigated different writing styles. “We used limericks to show poetry and rhythm,” says Sarah, “we used dialogue to start a conversation between the kids and their objects, we explored writing about time – last year, last month, etc – and we even used six-word stories to give them practice at writing to an exact number of words.”

The final workshop was dedicated to writing the children’s final pieces. “We told them they were completely free to write whatever they wanted about their object and in whatever style they liked,” Sarah explains. “One boy chose to write his piece about West Ham as a news article.”

An 11 year old boy was inspired by a West Ham shirt

Teletubby horror and Lily Allen bling

Children’s reactions to the museum objects were not always predictable. “There were a lot of laughs about the nappy, a lot of ‘bling’ references to the headphones and Lily Allen dress, and some of the girls were put off by the bra,” says Sarah. “But there were some darker elements too: many of them thought the Teletubbies were disturbing and they used them as the basis for horror stories. It’s interesting that the children saw them in that way, and goes to show that as adults we quickly lose touch with what really appeals to you as a child.”

“As kids, we’re driven more by our imaginations than by logic. But as we get older, we start to box ourselves in and give ourselves over to the logical part of our brains and become afraid of letting our minds run wild in all directions. Working with kids reminds me of the great fun you can have if you simply let go of the fear and give in to your imagination.”

“It kept on going nonsense!”

It wasn’t always easy for the children to get their ideas down on paper. One child said that the hardest part was writing the poem. “It kept on going nonsense!” For another, “The six word story was difficult because you couldn’t put descriptive words into it.”

But the overwhelming feedback was that this was a really enjoyable project. Asked what they liked best, the young writers said:

- “Going to the museum because it was so fun going round and looking at all the exhibitions. It was a different style of writing and exploring.”

- “Writing the 62 words because it’s tricky and gets you more interested… it’s more complex.”

- “I enjoyed the chance to come up with my own ideas.”

- “It has really kept my imagination going. It’s made me realise that there’s lots of different ways to write about feelings. It’s interesting how much power objects can give to your writing.”

- “I have always loved writing and I love writing stories. This has really inspired me.”

The kids got pretty good reviews themselves. “I love the pieces that our young writers have produced. They’re fresh, personal, fantastic,” says Lucy Macnab, Co-Director of the Ministry. Rhian Harris, the Museum’s Director and curator of the exhibition, is equally enthusiastic: “I think the children’s pieces are wonderful, really strong, inspiring stuff. They are going to provide a really important element to the exhibition – the child’s own response.”

Primary school, professional standards

Sarah was impressed by the way the children rose to the challenge of writing to a deadline and meeting the very precise word count – 62 words, no more, no less.

“The children tackled every exercise we gave them with enthusiasm and a lot of humour,” she says. “They had less than two hours to write, edit and deliver the final pieces. They all had clear ideas of what they wanted to say and were meticulous in getting the right number of words. In the end they met the deadline and hit a perfect word count. I reckon a lot of professional writers would have been stretched by that task.”

See the children’s writing at the Modern British Childhood exhibition at the Museum of Childhood until 14 April 2013.

This post originally appeared on the 26 Treasures of Childhood blog.